the spaces in between, 1/x

thoughts on narrative structure (Meander, Spiral, Explode & Cannery Row)

Cannery Row1 was my gateway drug. Perhaps that’s not entirely true (I was, after all, a poet for years before I read Cannery Row), but it is the moment I can point to and say, “I felt the spaces in between.”

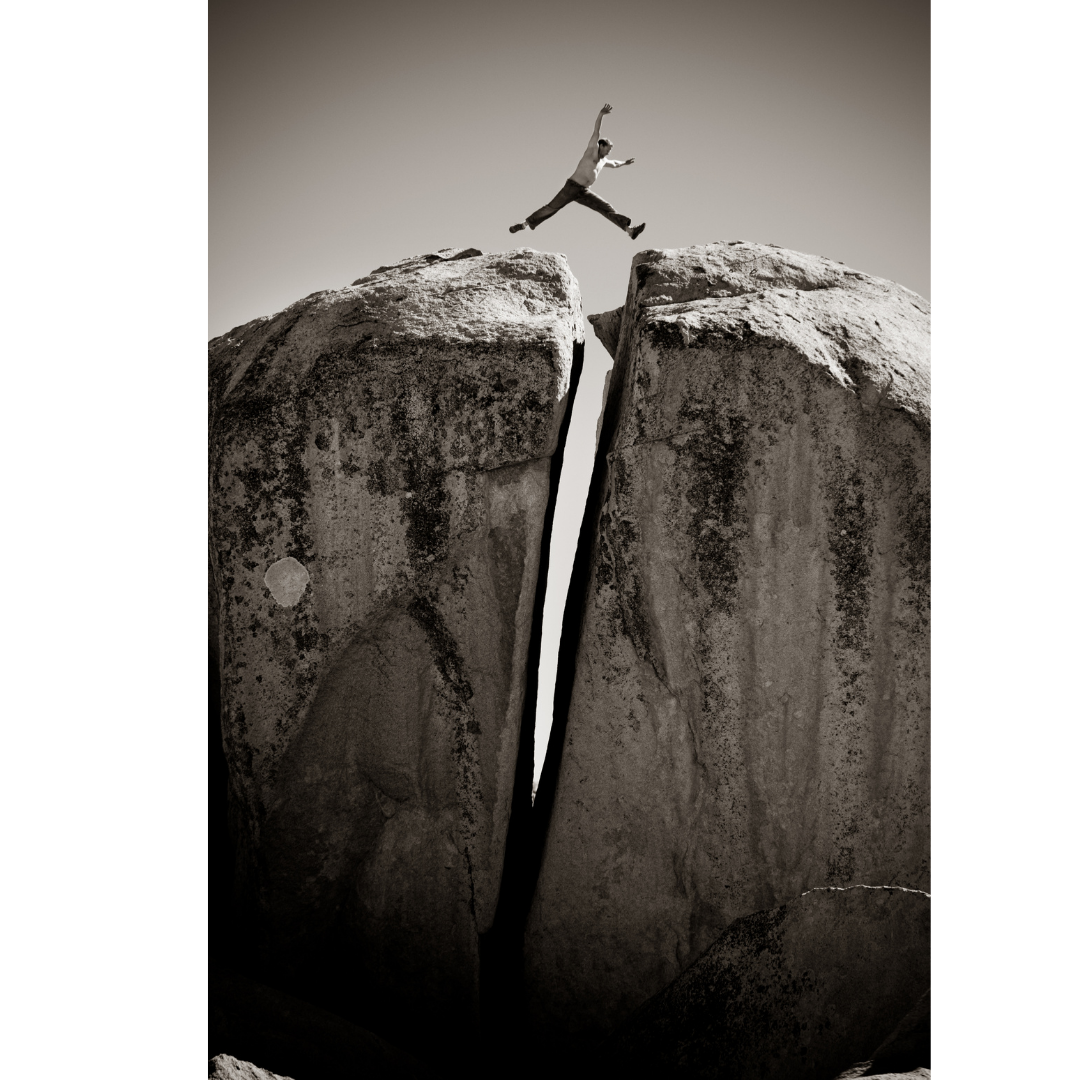

I love books that leave spaces: in the plot, in the characters, in the timelines, in the voice; books that invite us – the reader – to leap, to have faith, yes, but also to propel ourselves into meaning, rather than waiting for it to be delivered by the plot or the imagery or the characters.

I read Cannery Row for the first time in tenth grade with an English teacher who droned on about symbols for so long I couldn’t even hear the poetry of the book; the characters stiffened into didactic figureheads.

When I began teaching and saw it on the ninth grade reading list, I rolled my eyes. Cannery Row, first published 1945, tells the story of a group of “bums” in Monterey Bay. In short, vignette-like chapters, we watch the people of the town survive a flu, the indignities of poverty (slash-capitalism), addiction, loneliness, and a disastrous party that ends with a brawl and thousands of frogs released across town. While there are characters we see more often than others, there are no protagonists. In the prologue, Steinbeck writes that the way into Cannery Row is to “open the page and to let the stories crawl in by themselves”

Here is what I discovered when I read again: Cannery Row is episodic, cellular, like a beehive. In a more apt metaphor: it is a tide pool whose ecology is complete unto itself. Steinbeck provides few explanations for why the characters who populate the story are connected; in a way, Cannery Row the book mirrors Cannery Row the community: there is no grand, organizing principle – there are people in a place, and together they are greater than their individual stories. Mack and the boys mix liquor, adopt a dog, collect frogs, throw a party. Henri paints and dreams of ghosts. Doc finds a dead girl in the tides, drinks a beer milkshake, listens to music alone. Dora feeds the town. Lee Chong gives a man his dignity. The flagpole skater goes around and around.

Ronald Sukenick wrote that “[i]nstead of reproducing the form of previous fiction, the form of the novel should seek to approximate the shape of our experience.” This is what Cannery Row does.

And in embodying the form of the community in its structure, it asks the reader to participate in the creation of the book.

Away from the rigid buckets of literary devices, the characters and language returned to life. The chapters are short enough to read out loud and then discuss. What did you see? What did you feel? What did it remind you of? Does it seem true, based on your life? These are the questions my students and I asked of the text. We let each chapter dissolve in our mouths and hoped to discover: is there something in this I want to keep? Some chapters, for some readers, are duds and offer nothing, while other chapters sing and resonate. The same way, in a community, you aren’t going to love everyone.

I knew I couldn’t assign a literary essay; that formal, prescribed march through thesis and evidence seemed antithetical to the very structure of Cannery Row. So I offered them an ambitious challenge – one they rose to: a braided essay, weaving together their own life, Cannery Row, and another text of their choice (poem, song, moment in history, visual art, etc).

Braided essays create resonance between the “strands,” although their connections are not explicitly stated. Instead, the reader takes the leap, draws the lines, is made essential to the text in the spaces in between.2

In later years, I expanded the assignment: form came to mean not only the organization of the voices in their essay, but the physical object itself. Students created posters, illustrated books, even origami sculptures. Together, we played in the spaces in between and experimented with the meaning made by juxtaposition and intentional distances between texts.

Is there a word for this kind of text? One in which the reader must participate or the text itself is incomplete?

The closest I have come to an organizing principle that describes this kind of text is in Jane Alison’s Meander, Spiral, Explode.

We are all familiar with the dramatic, a structure which Alison traces from Freytag’s pyramid forward into Gardner’s Art of Fiction and which has become the assumed pattern for much of Western fiction. Conflict creates tension and forward momentum; pressure builds as the characters try and fail to change, until they either shed their initial identities or become entrenched, so that by the end we are sure the characters have arrived changed by what happened.

But what if, Alison asks, we sought out alternative shapes for fiction? Meander, Spiral, Explode explores those possibilities; Alison identifies and unpacks narrative structures that echo or mirror shapes in nature: waves and wavelets, meanders, spirals, radials, networks (like Cannery Row), and fractals.

What she sought, she writes, was “a way beyond the causal arc to create powerful forward motion in narrative: motion less inside the story than inside your mind as you construct sense.” These narrative shapes demand reader participation to find fulfillment.

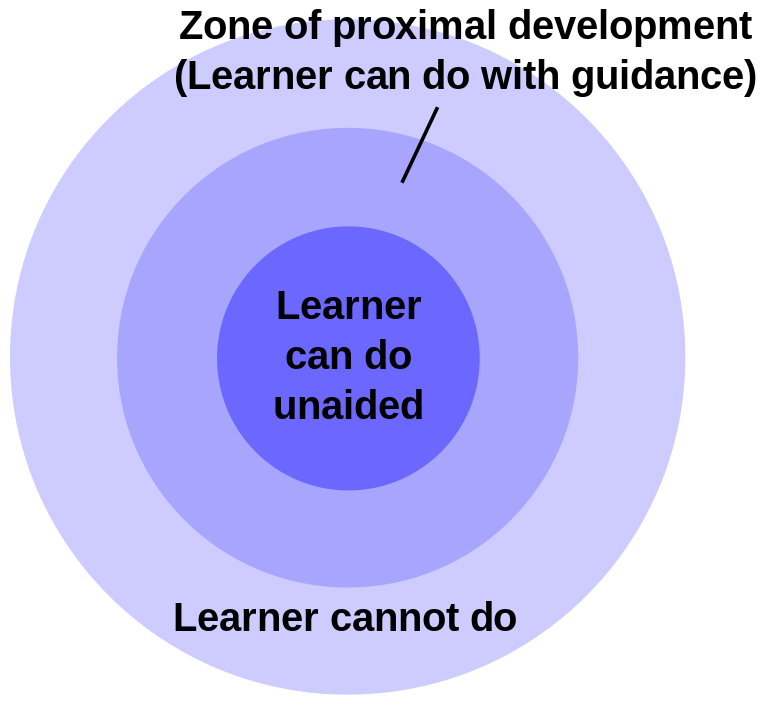

In reading this, I think of Vygotsky’s “zone of proximal development” (ZPD).

[The ZPD is] “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers”

It is through social interaction with the More Knowledgeable Other that we grow beyond what we could do alone.

What if texts that leave spaces, texts whose form and structure require the reader to take leaps – what if these texts act as a More Knowledgeable Other? What if their requirement of our participation is a kind of social engagement that leaves both participants changed?

Without the reader, what sense exists in Cannery Row? Without the reader it is just an assortment of portraits — a network of cells; in the mind of the reader, meaning is built.

I’m interested in how these stories function – how their parts fit together, how they work and how they fail. Although Cannery Row was the first text I consciously engaged with like this, many of my favorite novels belong to this category: stories whose structures mimic the organic world and leave space that the reader must cross alone.

In the next few months, I’ll use this newsletter to look back at some of those titles and explore what their structure is doing – and how I think it’s successful (or not).

Cannery Row contains several racist stereotypes about Chinese-Americans; when I taught the text, we examined the context of xenophobic and racist immigration laws and named Steinbeck’s dehumanizing language. That being said, I’m not sure I would have chosen it, had it not already been on the reading list.

My introduction to braided essays came through Eula Biss and her essay “No Man’s Land.” I also read and reread Jo Ann Beard’s “The Fourth State of Matter.”