13 thoughts on Literary vs. "Genre" writing

My eyebrows automatically raise when I hear anyone say “Literary vs Genre fiction.” A “genre” is a box we put a story into, based on the story’s plot and tropes, and to classify everything that isn’t literary as “genre,” seems a bit silly and snobbish. “Commercial” isn’t perfect, but it feels like a more specific term for what we’re talking about.

Dualities are appealing; they’re comforting. But the binary of “commercial vs literary” can’t accurately capture what’s happening in books (hence the birth of “upmarket”), nor does it do much to engage understanding and conversation — you’re either in or you’re out, one or the other.

I prefer a scale, although even scales are imperfect, since we tend to think of the two sides as opposites.

Some writers/readers argue that the scale is about plot- vs. character-driven stories, with plot-driven stories being more commercial, and character-driven stories being more literary.

Some of my favorite commercial books are romances. Everything that happens in a good romance is driven by character — their specific wants and flaws. The end of a romance is not satisfying or complete unless it is a resolution for the character (the plot does wrap up nicely, too, but it’s the character than matters). Romance characters are specific and emotionally rich, and romance is a primarily commercial genre. Given *waves hands at the romance genre*, the scale of plot- vs character-driven doesn’t hold weight for me.

I have also heard people argue that the scale is between “simply entertainment” and “navel-gazing with MFA frills.” I can practically taste the distain on both sides. This is dualism at work again — the idea that the “other” must be dismissed, devalued. I dislike the idea that literary stories are defined by “pretty prose” — as though it served no other purpose — or the idea that the more invisible prose of my favorite commercial books isn’t intentional — the product of smart, thoughtful writers.

this is maybe controversial but theres a BIG divide in genre fiction particularly between plot-forward writing and prose-forward writing. most sff readers prefer the former, most top sff writers are the former. lyrical sff is often called literary. there are few who can do bothEveryone is so angry about that Sanderson article, but I think it raises an important point about writing. If you examine the work of prolific and beloved writers at a sentence level, you will often find mediocre sentences. And that’s ok! Writing often just has to be invisible

this is maybe controversial but theres a BIG divide in genre fiction particularly between plot-forward writing and prose-forward writing. most sff readers prefer the former, most top sff writers are the former. lyrical sff is often called literary. there are few who can do bothEveryone is so angry about that Sanderson article, but I think it raises an important point about writing. If you examine the work of prolific and beloved writers at a sentence level, you will often find mediocre sentences. And that’s ok! Writing often just has to be invisible Moniza Hossain @moniza_hossain

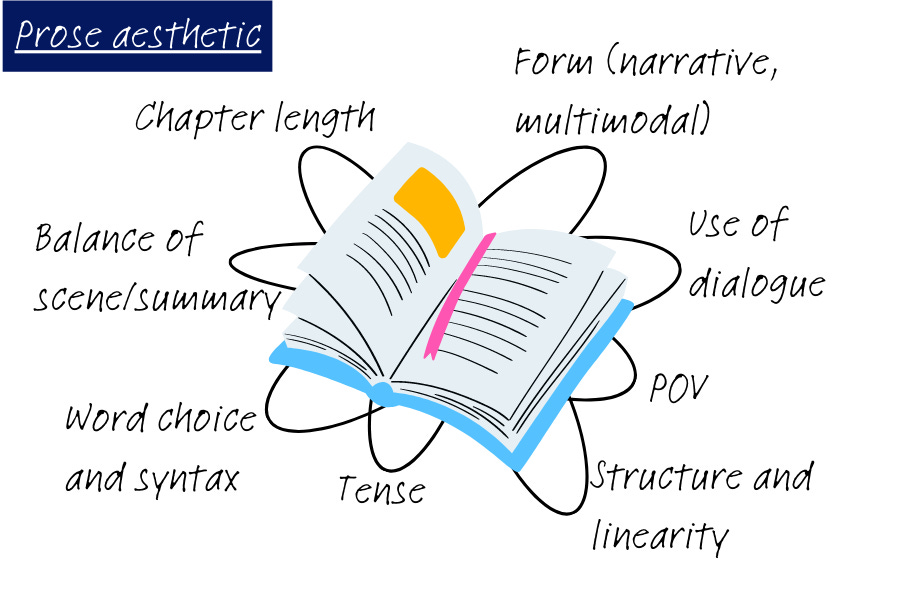

Moniza Hossain @moniza_hossainThe tweet above got me thinking about the function/visibility of prose (and I agree with her distinction), but this scale still seems to equate literary writing with lyricism and prettiness. So I have been toying with the idea of “prose aesthetic.” This sounds fancy, but it’s just the most specific term I could come up with. By prose aesthetic, I mean: everything that makes up how we experience the text, from the small (word choice, syntax, “linguistic ecosystem”1) to the structural (chapter length, linearity, form, tense, POV). I am talking about the tangible things you see on the page (presentation of the story), not the ideas of plot, character, or setting. It definitely has something to do with the difficult-to-define “voice,” but it is more than that. It has a kind of je ne sais quois to it.

Perhaps at one end of the scale, we have “prose aesthetic delivers the story” — by which I mean, the prose aesthetic is like a truck with the story in its bed, a separate thing being delivered. And at the other end of the scale, we have “prose aesthetic is a part of the story,” by which I mean — the form, the structure, the linguistic ecosystem, the linearity — are all actively telling some part of the story, the way the suspension cable is a part of the bridge.

I tried to make this argument to myself, and to place books on this scale (from “prose aesthetic tells story” to “prose aesthetic delivers”) and realized that — even for some of the most commercial fiction I’ve read, the prose aesthetic is still being used with intentionality to support the story.

So perhaps a better version of the scale is “prose aesthetic is visible” to “prose aesthetic is invisible.” When the structure, form, and language align with our expectations (based on genre?), they become invisible: the multi-POV 3rd person, short chapters, and clear language of a thriller serve and reinforce the story, but we don’t even notice them. On the other side of the scale, the fragmentation, frequent asides into memory, and idiosyncratic language of a book like Elizabeth Strout’s “Oh William!” call attention to themselves: we can see the prose aesthetic at work.

In this particular Discourse, it seems like the act of labeling is useful insofar as it helps us to understand and find books we’re excited about, but loses all utility when blunted into a tool of value judgement. I mean that going both ways — towards commercial and literary fiction. I am bored of the way we talk about “the other,” whichever side that is.

A more interesting conversation (at least to me) would be to move into a second dimension by adding another scale: perhaps “entertainment” to “discomfort” or “status quo” to “questioning” or “invitation” to “challenge” or “reader is a passenger” to “reader is a participant.” Or some other scale entirely. The problem of course, being that most scales are interpreted as opposites, rather than just different elements in a story — the way salt and sweet are not opposites in baked goods, although people prefer different balances of those flavors. Sometimes I want a pretzel; sometimes I want a cinnamon roll. Sometimes I want a salted caramel blondie.

Or maybe the more interesting conversation (the conversation I always want to have) is: What have you read lately? Did you love it? Why? Was it disappointing? Why? And on and on.

Shaelin Bishop talks about this in one of their videos